National Qualifications Frameworks in Africa: ACQF Survey 2024 - Report highlights main features and trends

NQFs in Africa in continuous development: Analytical Report of the ACQF Survey sheds light on key features, drivers of change, perspectives for further development in 29 countries.

Read the report and infographic summary.

New NQF survey

The first NQF survey conducted by ACQF-II is an update to the in-depth mapping study which launched the activities of ACQF-I in 2020, with a coverage of 14 countries and 3 regions.

The new survey (2024) received 51 complete responses, from 29 countries and gathered useful and diverse information on a wide range of features of NQFs, including objectives, levels, use of learning outcomes, governance and related policies.

The aim of the survey was to collect data and update the mapping of NQFs across Africa. The data will feed into the yearly-updated database on the state-of-play of qualifications frameworks in all African Union Member States and Regional Economic Communities. Thus, the results of the survey are instrumental in providing a broad overview of the landscape of qualifications and areas related to qualifications frameworks.

The survey included 48 questions of various types and utilised multiple display logics. The main branching of the survey was based on the NQF development level. Most questions were closed, single and multiple choice or involved importance ratings. Furthermore, the survey included several open-ended question and, in multiple cases, a text box option for requesting further detailed information or for cases when the respondent intended to give an answer outside of the predetermined list of options.

In total, the survey received 51 complete responses. Complete responses are considered those that have answered all obligatory questions and reached the end of the survey – thus, non-mandatory questions may not have been answered by all 51 respondents.

The total number of complete responses came from 29 countries. Subsequently, some countries received multiple responses. Initial data analysis made clear that these country responses were often conflicting. Throughout the report, we flag any such inconsistencies between respondents.

The questionnaire was structured into six main sections:

- Demographic and organisational aspects

- National Qualifications Framework (NQF) – Development and Governance

- NQF Characteristics

- NQF Credit systems

- Impact, needs, and lessons learnt on NQFs

- Regional Qualifications Frameworks

Summary conclusions

The online survey covered 29 countries (via 51 responses) out of the possible 55 African Union Member States. Below we summarise findings according to the main themes of the survey:

NQF level of development and governance: Departments and ministries of education, qualifications agencies or institutes are responsible for overall coordination and oversight of NQF development and implementation. Day-to-day running is usually handled by qualifications agencies or institutes, as well as departments or ministries of education.

Resources: Most NQFs are operated and sustained from state budget, but a sizeable share of them are also funded partly from international cooperation. Other types of funding are also present to a limited extent and 5 countries indicated to have no stable funding.

NQF characteristics:

- The primary legal basis for NQFs are usually laws or acts on NQF authorities or a decree on the NQF.

- Around half of the NQFs cover all sectors. Those with partial coverage usually do not include adult education.

- Furthermore, general education, higher education and TVET are the main sectors with separate sub-frameworks.

- Typically, NQFs have 10 levels, while some have 8 or more than 10 levels.

- National educational classifications, UNESCO classifications and national occupational classifications are the most used taxonomies.

- Knowledge, skills, competences and autonomy were the most frequently used domain descriptors across the countries.

- Around half of the respondents reported including non-formal or informal learning NQFs through the recognition of prior learning.

- Learning outcomes are present in curriculums in TVET most often but are present in all sectors to a high degree as well.

- A third of the countries with NQF have developed a database or registry. Half of these databases cover all sectors of education and training.

Credit systems: Credit Accumulation and Transfer Systems are not applied in the majority of the cases. If in place, the most covered sector is higher education, with lesser coverage of TVET or general education. The overwhelming share defined credits as equal to 10 hours of notional or study hours.

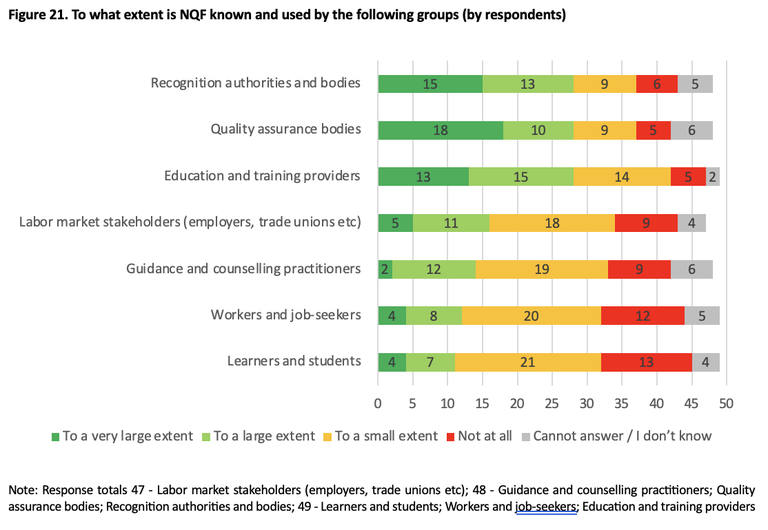

Awareness of NQFs: The awareness of NQFs by quality assurance bodies, regional authorities and bodies as well as education and training providers is considerably higher than other groups’. Labour market stakeholders, learners and students, guidance and counselling practitioners are less knowledgeable of NQFs.

Regional Qualifications Frameworks: The majority of respondents reported that an RQF is established in their region. Where an NQF is in place, most states have referenced their NQFs to the regional framework.

Zooming in the key features

Governance

Most often, Departments or Ministries of Education are the main organisations responsible for the overall coordination and oversight of NQFs (selected 19 times, or by 37.3% of the respondents). Alternatively, qualifications agencies or institutes (18, or 35.3%) are often the main responsible organisations as well. Other ministries may also be the main responsible body such as Departments or Ministries of Higher Education (8 respondents) or in Departments and Ministries of TVET and Occupations (8).

Other organisations (6 responses, such as qualifications authorities, boards or national council for technical and other academic awards), quality assurance and accreditation agencies (7) were some of the other frequently indicated organisations.

As opposed to the overall coordination of NQFs, day-to-day running is usually supervised more by qualifications agencies or institutes (21 or 46.7%) than ministries or departments. However, African countries tend to vary in this respect quite a lot. In more detail, other organisations that tend to be managing implementation and day-to-day running are: Departments or Ministries of Education (14 or 31.1%), Departments or Ministries of TVET and Occupations (9) as well as Education quality assurance or accreditation agencies (9) or other organisations (8).

Scope

Most NQFs were reported to have a wide coverage, including all stages of learning and development. Adult education was the most frequently not covered area. As follows, 19 respondents reported that general education, higher education, TVET and adult education is covered (or 42.2%).

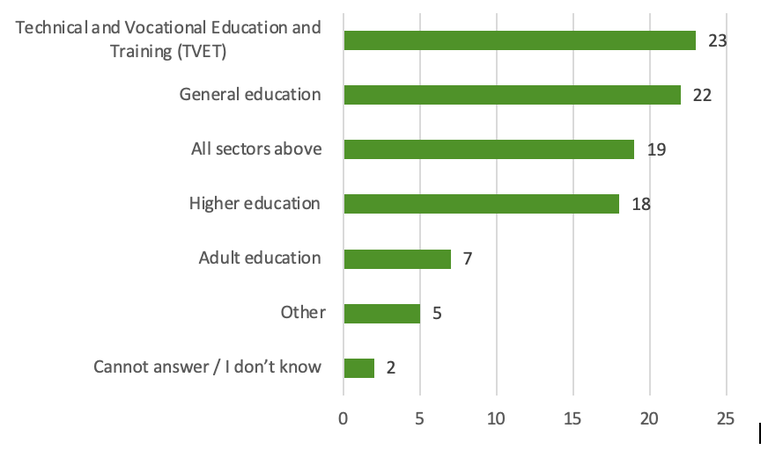

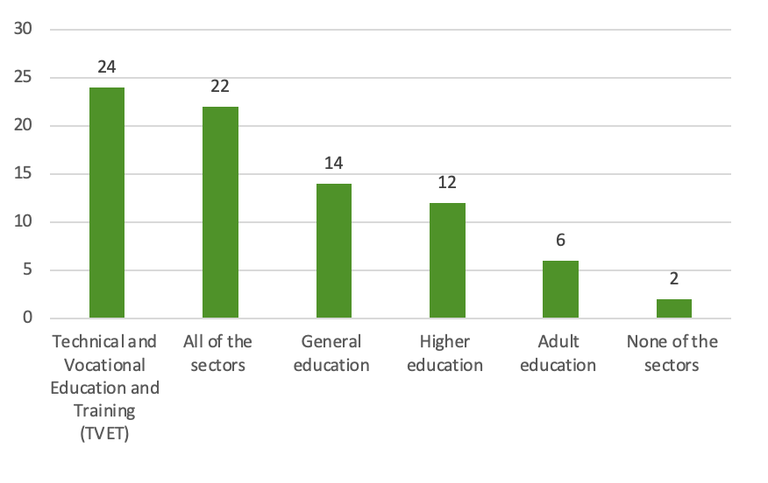

Figure 7. NQF coverage of various sectors (multiple choice, by respondents)

Roughly, the other half of respondents indicated that their NQFs do not cover all the indicated sectors. TVET (23 or 51.1%) and general education (22 48.9%) are the most often covered sectors in NQFs, while higher education was selected a bit less often (18) included. In turn, adult education is much less often covered in qualifications frameworks (only in 7 cases). Other areas that were mentioned were industrial skills or professional skills of other nature.

To summarise by countries, it is also visible that a large portion of the countries cover all sectors listed (13 countries), while in the case of those countries where the NQF is not entirely comprehensive, TVET sector is covered most often (13 countries), followed by general (8) and higher education (8).

Overall, the majority of the respondents indicated that their NQF is composed of different sub-frameworks. Nonetheless, some of the education and training areas are less often organised under a sub-framework. Most report that higher education (30 respondents or 78.9%), general education (29 or 76.3%) and TVET all have sub-frameworks (32 or 84.2%). Trades and occupations tend to have a separate sub-framework much less often (15 responses).

NQF Levels

The overwhelming majority of respondents reported that NQFs have 10 levels, with some fluctuation observed within the range of 8 or more than 10 levels. Accordingly, 32 responses (72.2%) indicated that their NQFs have 10 levels. The second most frequent is NQFs with 8 levels (5 responses), followed by those frameworks that have more than 10 levels (3 responses). NQFs with less than 8 levels were highly uncommon. To list these out, Ghana and Tunisia indicated to have less than 8 levels in the framework (see table below on the country-by-country summary).

Level descriptors

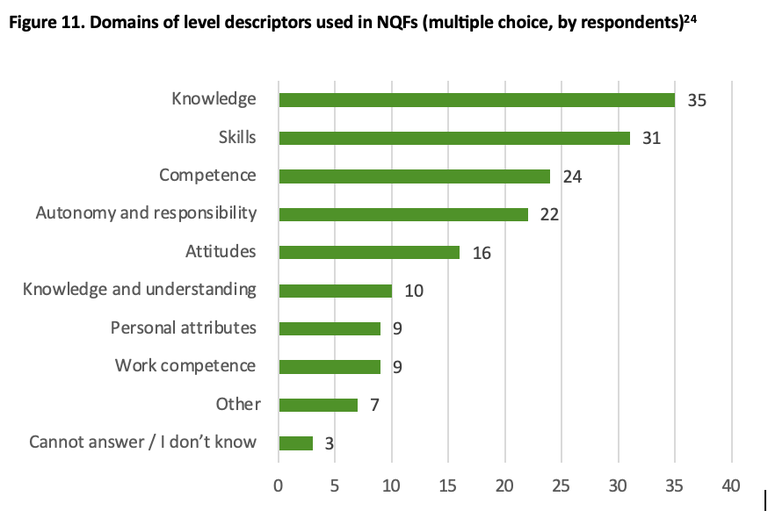

Level descriptor domains are used to differentiate types of learning and learning outcomes captured in NQFs. As the figure 11 illustrates, there are multiple such domains used in African countries to describe learning outcomes.

The four most frequent descriptors are knowledge (35 or 79.5% of respondents), skills (31 or 70.5%), competence (24 or 54.5%) and autonomy and responsibility (22 or 50%).

Somewhat less frequently, but other level descriptors are utilised as well, such as attitudes (16 or 36.4%), knowledge and understanding (10 or 22.7%), work competence (9) or personal attributes (9). Lastly, among other types of descriptors, reasons and problem-solving, the degree of complexity of tasks, autonomy, and responsibility were mentioned.

Countries usually have at least three types of descriptors. In line with the previously discussed results, the most popular are: knowledge (used in 21 countries), skills (19), competences (16) and autonomy and responsibility (16).

Eight kinds of descriptors, the highest number overall, are used in Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Sierra Leone and South Africa. The least number of different descriptors are used in Angola, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Malawi, Somalia and Zambia.

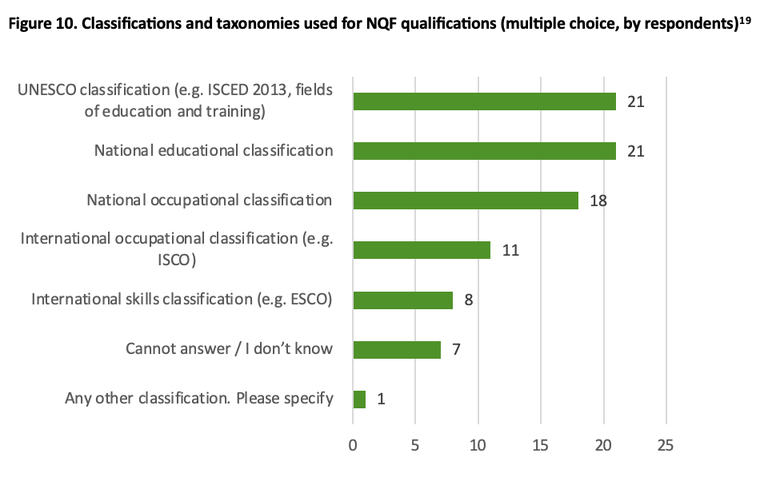

Used international classifications

Organising education programmes, related qualifications or information on education in general might be performed based on various classification systems, that usually distinguish different levels of education.

The results show that UNESCO classifications and national educational classifications are applied in identical frequency (21 responses or 41.2%) for NQF qualifications.

The results show that UNESCO classifications and national educational classifications are applied in identical frequency (21 responses or 41.2%) for NQF qualifications.

Other types of taxonomies and classifications are used in varying degrees. To a slightly smaller extent, national occupational classifications are the third most used classificatory systems (18 responses, 35.3%).

In turn, international classifications are less recurrent: international occupational classifications have been implemented for NQF classifications in 11 cases, while international skills classifications in 8 cases.

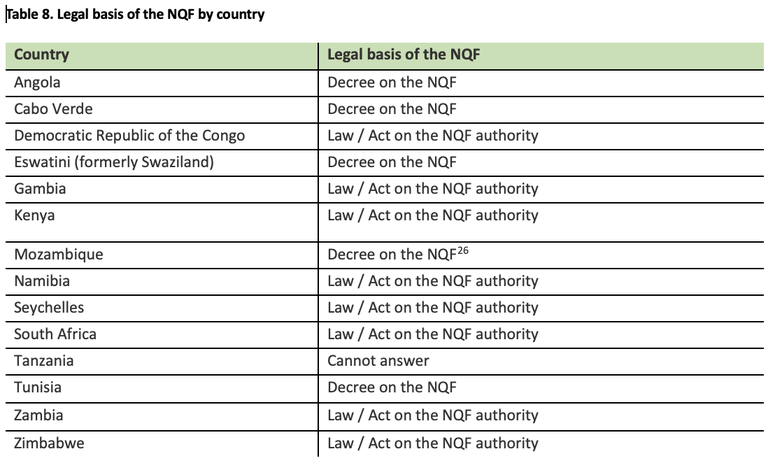

Legal basis of NQF

Qualifications frameworks may be established through different legal instruments or other types of (preparatory) documents. Respondents from countries with an NQF established indicated that the primary legal bases are a law or act on the NQF authority (14 responses) or a decree on the NQF (8 responses).

One respondent indicated that there are guidelines on registration of qualifications, serving as a legal basis while one more respondent could not answer the question. From a country-by-country perspective, In most countries with an established NQF, a law or act is the main regulatory document (8 cases), while a decree is also frequently used (5 countries).

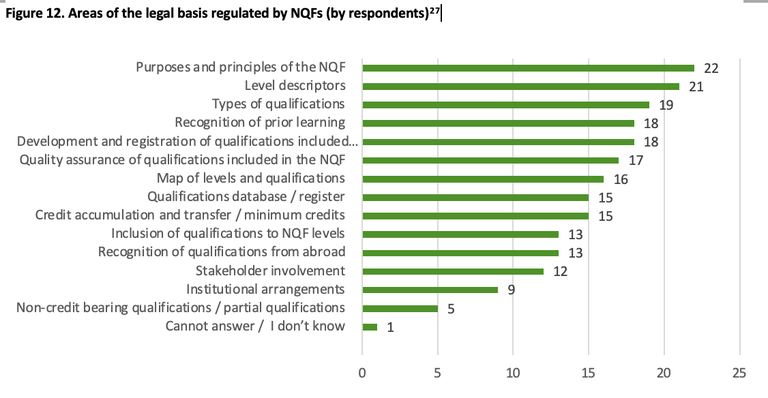

Furthermore, respondents were asked about the specific areas regulated by NQFs (see Figure 12 below), most of which are included in at least half of the cases.

This shows that certain areas tend to be widely covered by regulation. More than two-thirds indicated that the purposes and principles of NQFs (included in 22 times or 95.7% of responses to the question), level descriptors (21 responses or 91.3%), types of qualifications (19 or 82.6%), development and registration of qualifications (19 or 82.6%), map of levels and qualifications (16 or 69.6%) and quality assurance of qualifications (17 or 73.9%) are covered in the legislation.

On the other end of the spectrum, institutional arrangements tend to be less covered (9 responses or 39.1%), alongside non-credit-bearing or partial qualifications (5 or 21.7%).

Objectives of the NQF

Three of the most important objectives of NQFs:

- The harmonisation and integration of national qualifications systems (89.4% or 42 respondents indicated to be at least important or very important)

- The international comparability and transparency of qualifications and mobility (89.6% or 43 thought to be at least very important).

- Improving the value of technical and vocational qualifications (89.4% or 42 respondents)

Five of the other surveyed possible objectives received a somewhat lesser but still high importance rating of between 80-90%:

- International mobility of students and workers, selected by 43 respondents

- Lifelong learning, selected by 41 respondents

- Progression and flexible pathways, selected by 41 respondents

- Quality assurance of qualifications, selected by 41 respondents

- Recognition of (prior) learning, non-formal and informal learning, selected by 39 respondents

In comparison, three other possible objectives were less frequently selected, receiving an importance rating of around 70%:

- Linking supply and demand, selected by 37 respondents

- Redressing past injustices, selected by 32 respondents

- Joint development of qualifications with other countries, 33 respondent

Given that most objectives are widely supported, countries may be differentiated in relation to less popular objectives. Accordingly, responses from Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Namibia think that the joint development of qualification with other countries are less important compared to the other items in the question. Furthermore, responses from Nigeria, South Sudan, Uganda and Zambia reported that redressing past injustices are unimportant. However, most of these countries do not have a developed NQF, hence the relatively importance of other objectives.

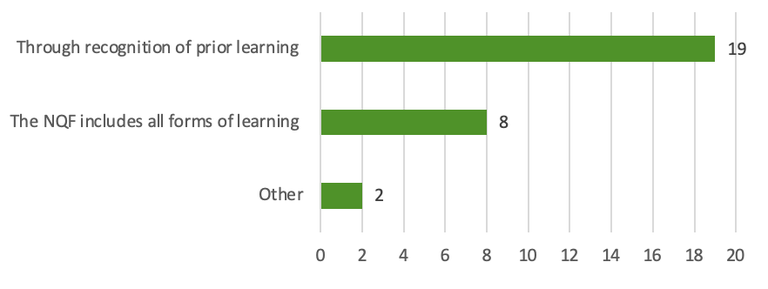

Non-formal and informal learning in the NQF and the place of learning outcomes

Non-formal and informal learning is part of the NQFs systems in 19 cases. Most often, these forms of learning are included through the recognition of prior learning (18), while in some cases, NQF includes all forms of learning (8).

Figure 14. Representation of non-formal and informal learning in the NQFs (by respondents)

In most cases, qualification frameworks are based on learning outcomes (43 responses or 87.8%), while one respondent indicated a negative response and 5 did not know how to answer. This observation is true for 26 countries, while 3 could not answer the question.

Furthermore, the figure below summarises education and training sectors within which learning outcomes are used in curriculum.

Figure 15. Usage of learning outcomes in curriculum by education and training sectors (by respondents)

In almost half of the cases (22 responses or 44.9% of those who answered the question) learning outcomes are used in all of the relevant sectors, ranging from general education to adult education.

With regards to specific education and training sectors, in cases where not all sectors are covered, learning outcomes are most often used in TVET curriculum (24 responses or 49%), general education (14 respondents or 28.6%) and higher education (12 responses or 24.5%). Learning outcomes are much less regularly used in adult education (6 responses), while 2 respondents (from Angola and Senegal) said that none of the sectors are using learning outcomes.

Quality Assurance

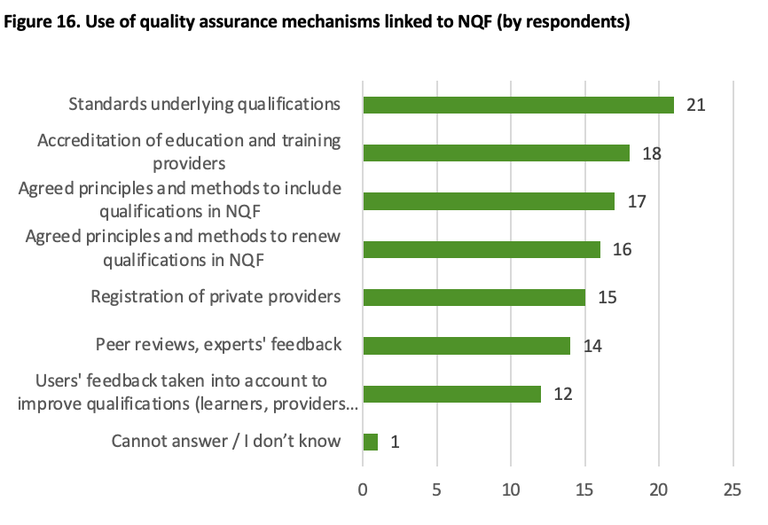

Responses indicate that certain quality assurance features are more typical for African countries with NQFs.

Standards underlying qualifications (21 responses or 91.3%), accreditation of education and training providers (18 responses or 78.3%) and agreed principles and methods to include qualifications in NQFs (17, 73.9%) are the most typical quality assurance mechanisms.

However, other features such as the registration of private providers (15 or 65.2%), agreed principles and methods to renew qualifications (16, 69.6%), peer reviews and experts’ feedback (14, 60.9%), as well as users’ feedback to improve qualifications are often used solutions as well.

Angola, Cabo Verde, the Democratic Republic Congo, Mozambique and South Africa indicated to be using all of the listed quality assurance mechanisms, while Namibia, the Seychelles and Zimbabwe indicated to use a part of the mechanisms.

Impact and visibility of NQFs

Awareness on NQF

Quality assurance bodies and relevant recognition authorities and bodies are by far the most aware of NQFs. According to the perception of respondents:

- 3% of the quality assurance bodies know and use NQFs to a very large or large extent

- 3% of the recognition bodies and authorities know and use NQFs to a very large or large extent

- 1% of the education and training providers know and use NQFs to at least a large extent.

Other stakeholder groups have a more limited knowledge and are placed at similar levels of awareness. Subsequently, respondents reported that the following share of the stakeholder groups are at least knowledgeable or using NQFs to a large extent:

- 34% of the labour market stakeholders,

- 2% of the guidance and counselling practitioners,

- 5% of the workers and job-seekers,

- 4% of the learners and students.

While NQFs are fairly well-known in the case of professionals whose work is connected to NQFs more directly across all countries, the perceived levels of awareness tend to vary in the case of the other groups. Below, we provide some further country-by-country information for each of the less aware groups:

- Labour market stakeholders were reported to be the most knowledgeable of NQFs in Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa and South Sudan, while least aware in Angola, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Somalia and South Sudan

- Guidance and counselling practitioners were seen as aware to a large extent in Nigeria and South Africa, while the opposite was reported about them in Angola, Ethiopia, Ghana, the Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan and Uganda

- Workers and job-seekers were reported to be aware of qualifications frameworks to a large extent in Gambia, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe, while the contrary was reported in case of Angola, Burkina Faso, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan and Uganda

- Learners and students were seen as aware to a very large extent in case of Gambia, South Africa, Sudan and Zimbabwe and not aware at all in Angola, Cameroon, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia and South Sudan

Future plans in respect to NQFs

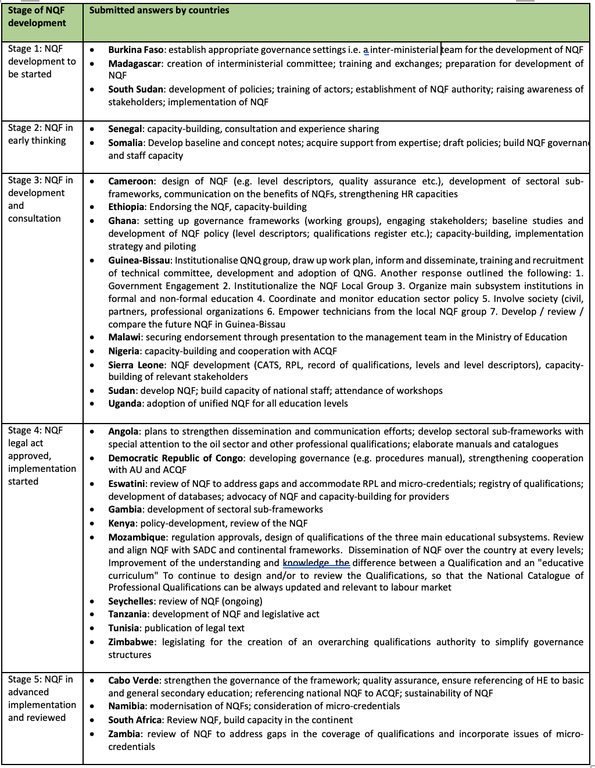

Based on the open question, the table below summarises respondents' plans with regard to developing NQFs further.

Table 12. Summary table of countries’ future plans with regard to their NQFs